PhD Research:

My research interests are in Inference, Modeling/Simulation, Control, and Learning applied to Robotic Manipulation. I am interested in the complex and exciting world of physical interactions, these interactions are fundamental to the utility of real-world agents. Physical interactions are complex because they are hybrid, which means that the dynamics of the robot change as it comes into contact and whether the type of contact is permitted to stick or slide. These interactions are also difficult to model because of the complex nature of frictional contact. Though contact is complex, it provides us with a wealth of information which we can use to make inferences about the world.

I develop algorithms and models that allow robots to intelligently and autonomously interact with and learn from their environment in the real-world. I have worked on both model-based and machine learning approaches and believe there is a world in which we can combine our knowledge of physics and data-driven approaches to garner the best of both worlds.

Why Manipulation? Manipulation is key to realizing the promise of robotics: a solution to some of society's biggest challenges -- including patient care, industrial automation, and disaster response. Central to these challenges is a robot's ability to control its environment through selective contact and yet, despite its importance, manipulation is still an open problem. As robots touch their environment, they change it. The characteristic challenge in manipulation is that robots have to reason about and cause this change in partially unknown environments using noisy and incomplete sensory information. How do we build agents that reason about this change intelligently?

Some of the projects I have worked on:

Hierarchical Manipulation Skill Learning

As humans, we are able to seamlessly integrate our senses of sight and touch to learn about our physical world. These two modalities provide complementary information, for where sight provides global but coarse information, touch provides dense and highly descriminative but very local information. Not only do we see and feel our world, but we also catagorize and build useful abstractions to facilitate our manipulation skills. For example, when interacting with a door, we may infer it is locked or open (two useful abstractions we have constructed) through how it feels and moves. In this project, we explore how to enable a robot to autonomously build useful abstractions and physics models, in the joint domain of touch and vision, for a robot learning the mechanics of Jenga.

Jenga captures some of the essential challenges in robotic manipulation: i) it requires sight and touch to be played, ii) it is a partial information game, iii) tower resets are expensive and time-consuming so data efficiency is critical. To touch on partial information, just from vision, it is practically impossible to tell which blocks move and which don't. This is because the mechanics of block motion are governed by micro-frictional interactions and weight distributions that are unobservable with the visual data-stream. The only way to recover necessary information is through interaction. We demonstrate that the robot is able to learn useful abstractions such as blocks that move easily or are stuck, and uses this information together with motion models to accurately and carefully extract blocks.

Science Robotics 2019 Jenga Video 2019

Inferring robot parameters & contact forces during frictional interactions

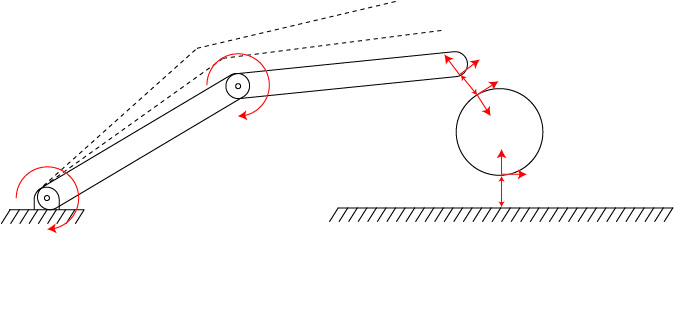

Let's assume we have a rigid-body system (for example a robotic manipulator) making and breaking contact with the environment. How can we infer physical properties such masses, inertias, and contact properties simultanously with contact forces? Most importantly, how can we infer these properties without breaking the trajectory into contact-free and contacting segments and individually studying each? Is there a way in which we can consider the full trajectory of the system including contacts in one framework?

In this project, we developed a mathematical framework that: i) tells us explicitly what parameters/forces are identifiable given the types of observations available, and ii) provides a formulation to compute these quantities given a time-series of observations under the assumption of rigid-body frictional interactions without the need to explicitly identify and enumrate contact events. This formulation yields a nonlinear optimization program that can be solved for the desired properties given noisy state measurements.

Rigid-Body Contact Modeling: Identification, Evaluation, & Comparison

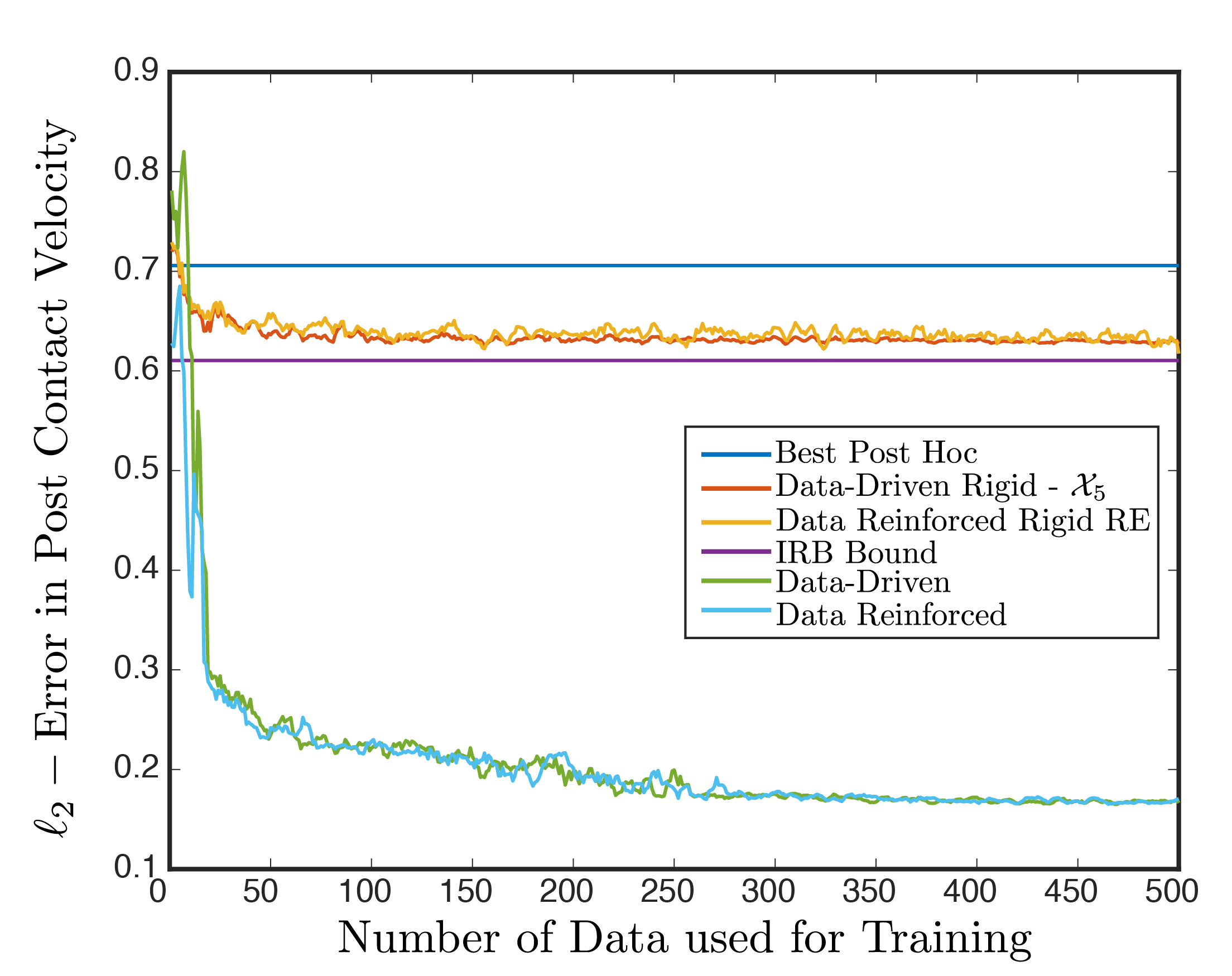

Rigid-body contact models are extremely important to predicting, planning, and control of robotic interactions adn serve as the foundations to many simulators. An important lesson we learned during the parameter and force identification project was the variable sensitivity to the particular model choice. In light of this, we decided to compare 6 commonly used rigid-body contact models using the time-stepping complementarity formulation and evaluate their predictive abilities empircally.

In this project, we: i) developed a principled formulation for contact model parameter estimation using the Energy Ellipse, ii) compared the predictive performance of the models on an empirical planar impact data-set (publicly available), and iii) showed the challenges in model identification and issues of predictive performance, in particular by showing an empirical upper-bound on the performance of these models and a theoretical upper-bound on the task for which no model generated from the rigid-body approximation can breach. Our findings served to highlight challenges in contact modeling and that simulations are perhaps not as reliable as we hope or like to believe.

Data serves as a critical component to the evaluation and development of models (whether data-driven or analytical). In a parallel project to the planar impact experiments, we collected the largest experimental planar pushing data-set available in robotics. We collected planar pushing data for a wide variety of surfaces, speeds, and objects. This data-set has found great utility in the community for model learning, validation, and controls.

Learning Data-driven & Data-augmented Contact Models

Frictional interaction is a complex and difficult to model phenonemon. In building computationally efficient contact models, two key issues affect fidelity: i) we make a set of assumptions for simplification and tractability, and ii) we cannot observe or model all features necessary to capture the minute but important details of interactions.

Learning Corrective Contact Models for Predictive Performance:

One approach to maintaing efficiency but improving fidelity is to let the data speak for itself. In these projects, we explored the use of data-driven and data-augmented models for contact interactions. In particular, we utilize combinations of analytical techniques and data to build sample-efficient and high-fidelity models that can be used for prediction or controls. The first figure shows the 3 fold improvement in predictive performance over the state-of-the-art models for planar contact if we combine them with data-driven models.

Learning Corrective Planar Manipulation Models for Controls:

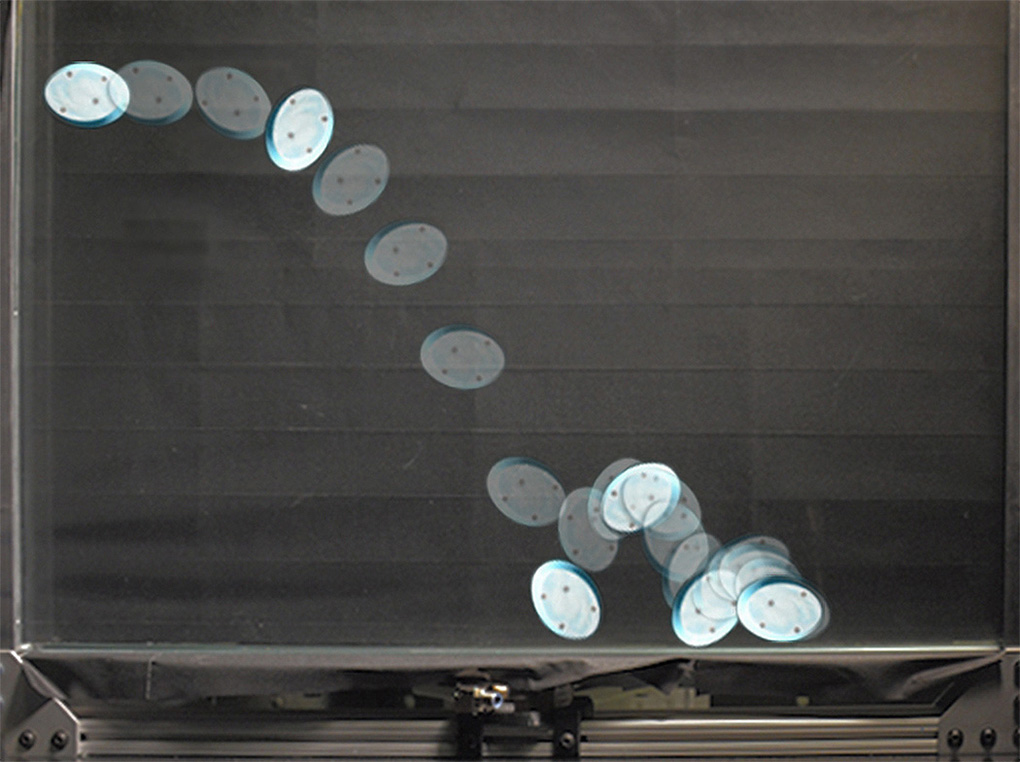

In the second figure, the goal of the robot is to guide the secondary disk to a goal position by pushing on the primary disk using its end effector -- a challenging task for which analytical models perform poorly. The robot uses experimental data to learn a residual (corrective) model to a physics engine for the contact interaction between the two disks and the surface. It then uses this data-augmented model to perform model-predictive control to push the second disk to a goal using the first disk.

An important detail in model-predictive control is reliable long-horizon planning. The data-augmented model we developed uses a stochastic recurrent formulation which provides better accuracy in long-term prediction over the more traditional single-step models that accumulate error. The residual model is also augmented with mild domain randomization in simulation and the algorithm is able to achieve the task reliably with just 2000 samples, 1500 simulated randomizations and 500 experimental single-step pushes. This task is an example of a difficult planar manipulation problem with many hybrid modes for which analytical models struggle.

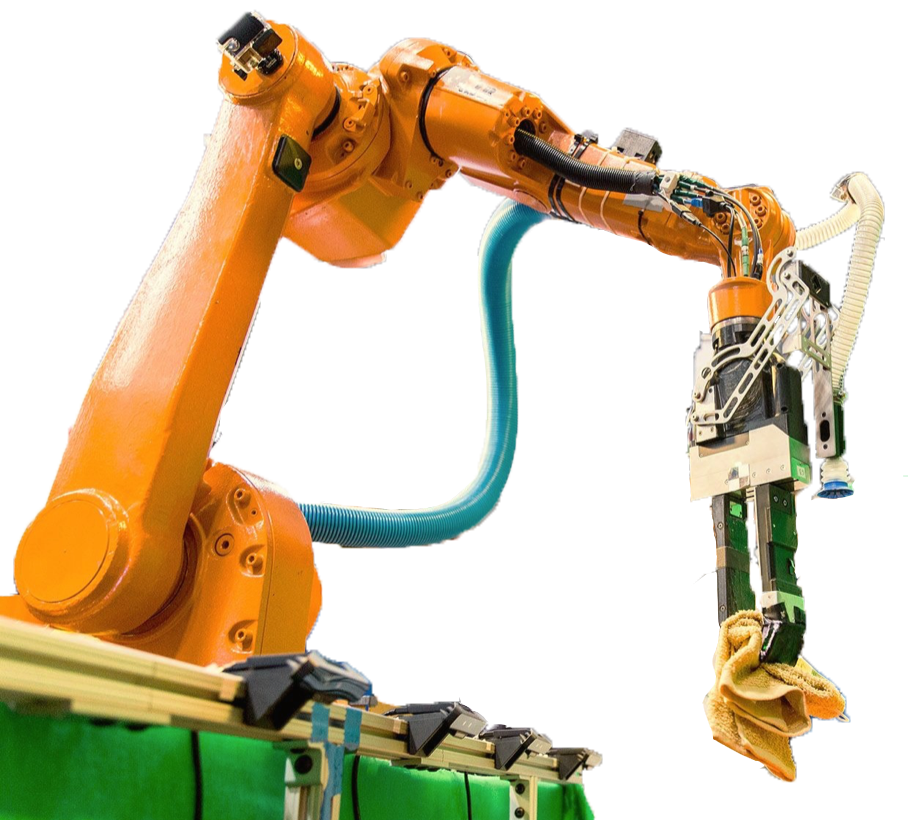

Robotic Pick & Place

An important challenge in warehouse automation is automating the process of finding and moving objects desired objects from one place to another. We developed an autonomous system that does exactly this and competed in the Amazon Robotics Challenge (2015-2017), with consistent top 3 placements and winning 1st place in stowing in 2017.

The key challenge here is that the robot does not know what the majority of objects are prior to interaction. As such, it needs to understand which objects to go for, and which modality of manipulation it needs to employ for success. Watch our video for more information. Building and developing robotic systems for industry has two key benefits: developing strong practical expertise and grounding research in real-world applications. The challenge provided us with a unique opportunity to understand industry needs and strengthen our relationships with our industry partners. In particular, the challenges in object state and parameter estimation in highly-cluttered and partially observable scenarios has served as inspiration for my research.

Masters Research:

During my masters, I worked on Inference, Modeling/Simulation, Control, and Learning applied to the Human Cardiovascular System and pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetics. Modeling these systems is particularly challenging but has potentially large impact in disease diagnosis and preventative medicine.

System identification and machine learning are important tools that enable us to predict and infer diseases and are critical to diagnosis. These tools enable detection of abnormalities that are central to diagnosis and preventative care.

Here are some of my previous projects:

Estimating Cardiac Output and Peripheral Resistance

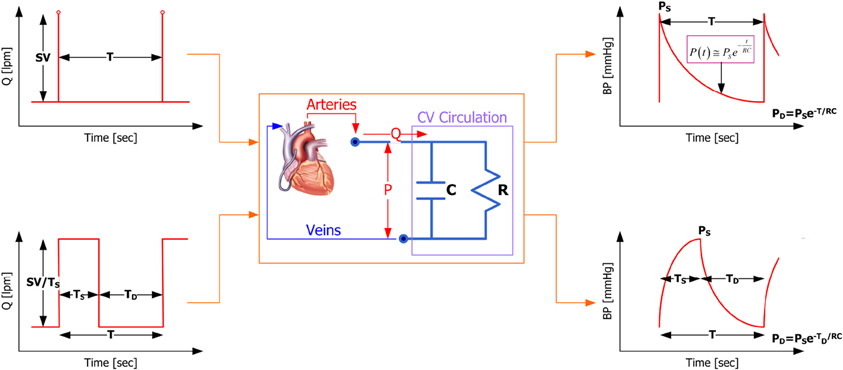

One model for the human arterial tree is a simple lumped RC network, where the heart acts as a voltage source and the arterial tree acts as a capacitor/resistor. In this project, assuming that this model holds, we estimate the cardiac output of the heart and the peripheral resistance provided by the arterial tree using in-vivo measurements from swine.

In particular, in this study we showed how using a square-wave as the voltage source for the heart does a better job of estimating the cardiac output and provided a formulation for the estimation of the parameters and cardiac output. Modeling the arterial tree using simple models gives us the ability to track cardiac health with data-efficient methods that can serve as the basis to more sophisticated diagnosis tools.

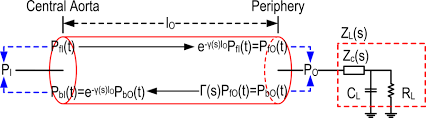

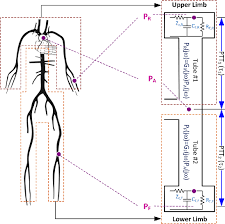

Cardiovascular Modeling and System Identification

The Tube-Load (TL) model is a well established and relatively complex approximation for the human cardiovascular system. In this sequence of studies, we investigated the fidelity and identifiability of these models on first swine, then humans. In particular, we showed that these models are effective in predicting peripheral and central blood pressures and can reliably estimate the time required for a blood pressure wave to propagate along the upper or lower body conduits.

These studies laid the foundation to future work in which we used these models to detect anomalous stiffness or delay in wave propagation that can be indicators of cardiac health.

ACC 2013 JBE 2013 DSMC 2013 JBE 2014

Central Aortic Blood Pressure Wave-Form Estimation

Given the fidelity of the TL model in representing wave propagation in the human arterial, we looked at ways in which we can leverage it for diagnostics and preventative care. In the first set of studies, we investigate the blind recovery of the central aortic blood pressure from two peripheral blood pressure measurements using these models. We showed that it is possible to fully identify the TL model parameters and recover the central BP with high fidelity.

The measurements utilized in these studies was invasive and entirely dependent on the frequency content of the waves generated by the heart. We showed that these waveforms, previously measured invasively, are recoverable from oscillations in a blood pressure cuff. We also showed the theoretic possibility of exciting the arterial tree with the cuffs to super-impose waves onto the BP to recover higher fidelity models.

Pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetics of Diabetes in Humans

Pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetics describe the way in which medication and its effects propagate through the body. In particular, they relate the dose and time of dosage to the propagation and concentration of the medication in the body. Further, they model the effects of the medication on various end-point measures. For example, patients with diabetes consume a dosage of insulin that then affects several end-point responses.

In this study, we proposed a novel method to derive data-driven model of pharmacological systems that is built upon information fusion of endpoint responses. We show the system's identifiability by analyzing a relation between endpoint responses and demonstrate that it is fully identifiable in case all the responses involve effect compartments. We demonstrate the efficacy of the method on several benchmark pharmacological modeling problems. This approach is an important step towards tailoring drug dose to a patients physiology.

</div>